33 KiB

| created_at | title | url | author | points | story_text | comment_text | num_comments | story_id | story_title | story_url | parent_id | created_at_i | _tags | objectID | year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018-02-07T23:42:36.000Z | The Birth of a Psychedelic Culture (2010) | http://realitysandwich.com/34204/beginning_birth_psychedelic_culture/ | pmoriarty | 50 | 3 | 1518046956 |

|

16328988 | 2010 |

The Birth of a Psychedelic Culture - Reality Sandwich

Reality Sandwich

[

Evolving consciousness,

bite by bite.

V2.2

]1

| ----- |

| __ Login | __ Signup |

|---|---|

Remember

| |

Yes!

__

/psyche Psychedelics __ Psychedelic Culture Longform

__ Share

__ Share Link**

Use this link for email & social media, & receive 1 Share Karma point for each person who follows the link.

The Birth of a Psychedelic Culture

![]() John Perry Barlow • 8 years ago • __ 1 Comments

John Perry Barlow • 8 years ago • __ 1 Comments

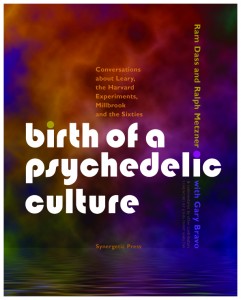

The following is excerpted from the Foreword to Birth of a Psychedelic Culture: Conversations about Leary, the Harvard Experiments, Millbrook and the Sixties, by Ram Dass and Ralph Metzner with Gary Bravo, from Synergetic Press (Through Sun Feb 9th, enter discount code “reality” at Synergetic Press’s site and receive 35% discount on this title, after purchase you will receive an e-mail with ANOTHER code for a FREE e-book of your choice, including ‘Mystic Chemist’). Also available through the Evolver Network.

LSD is a drug that produces fear in people who dont take it. –Timothy Leary

It’s now almost half a century since that day in September 1961 when a mysterious fellow named Michael Hollingshead made an appointment to meet Professor Timothy Leary over lunch at the Harvard Faculty Club.

When they met in the foyer, Hollingshead was carrying with him a quart jar of sugar paste into which he had infused a gram of Sandoz LSD. He had smeared this goo all over his own increasingly abstract consciousness and it still contained, by his own reckoning, 4,975 strong (200 mcg) doses of LSD. The mouth of that jar became perhaps the most significant of the fumaroles from which the ’60s blew forth.

Everybody who continues to obsess on the hilariously terrifying cultural epoch known as the ’60s — which is to say, most everybody from my “gege-generation,” the post-War demographic bulge that achieved permanent adolescence during that era — has his or her own sense of when the ’60s really began.

There are a lot of candidates: the blossoming pink cloud in the Zapruder film, Mario Savios first speech in Sproul Plaza, the passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, the Beatles’ first appearance on the the Ed Sullivan Show, the first Acid Test, the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park, the release of the song Good Vibrations, the day Jerry Garcia got kicked out of the army.

But as often as not, if you are a Boomer, the ’60s began for surreal on the day you dropped acid.

And if that is when the shit hit your personal fan, you may owe a debt of ambiguous gratitude to the appealingly demonic young sociopath who conveyed the Stark Bolt of Chemical Revelation to the nice young gentlemen of the Harvard Psilocybin Project.

The essential tameness of the group that was to become so notorious is only one fascinating feature of discourse to follow between the Projects second and third most celebrated veterans: Ram Dass (who as Richard Alpert, PhD, was Tom Sawyer to Tim Leary’s Huckleberry Finn) and Dr. Ralph Metzner (who began as an acolyte and wound up presiding over the remains).

All Rights Reserved

In some of the photographs in this book, taken prior to the arrival of Mr. Hollingshead and his Magic Mayonnaise Jar, the learned investigators are actually whacked on psilocybin and yet, their narrow black ties are still neatly knotted, their horn-rimmed glasses are on straight, their earnest civilization is still visibly intact. Consider that Dr. Alperts first impulse, upon regaining the ability to walk during his first psychedelic experience, was to head off through the snow to his parents house and start shoveling their driveway. Upon being discovered, his defiant response was to dance a jig. This is truly a rebel without claws.

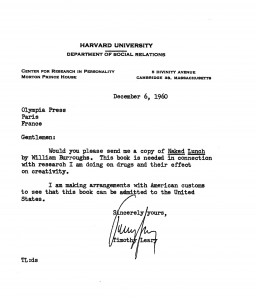

Naked Lunch Letter (All rights reserved)

But a few days after that fateful lunch with Hollingshead, Timothy Leary dropped acid and everything changed. The sober, scientific center of the Harvard Psilocybin Project lost its hold on the centripetal edge. The past started to end and the future started to begin. Their ties loosened and disappeared, along with belief in any such prosaic artifact as objective reality and the social conventions that accompanied it. As Leary later wrote in High Priest ( p. 256-257 ):

From the date of this session it was inevitable that we would leave Harvard, that we would leave American society and that we would spend the rest of our lives as mutants, faithfully following the instructions of our internal blueprints, and tenderly, gently disregarding the parochial social inanities.

Ram Dass had a somewhat more alarmed reaction:

When Tim first took LSD, he didn’t speak for weeks. I went around saying, ‘We’ve lost Timothy, we’ve lost Timothy.’ I was warning everybody to not take that drug, because Tim wasn’t talking and he was sort of dull When I took it, I felt it went so far beyond the astral, beyond form, to pure energy. It showed me that in previous psychedelic sessions, I had been screwing around in the astral plane. LSD was no nonsense. If you weren’t grounded somewhere, you’d go out on this drug.

They were both right, of course. These were by no means unusual responses to the experience. Thanks in very large part to the subsequent exertions of Drs. Leary, Alpert and Metzner, the experience was one shared over the following decade by tens of millions of Americans, the larger part of whom found it difficult ever after to take seriously the verities that few in Eisenhower’s America would have questioned. Our paradigm got fucking well shifted.

At least mine certainly did. And so, I would venture, did that of the United States of America, during the trip we took between 1961 and 1972.

One can make a non-ludicrous case that the most important event in the cultural history of America since the 1860s was the introduction of LSD. Before acid hit American culture, even the rebels believed, as Thoreau, Emerson and Whitman implicitly did, in something like God-given authority. Authority, all agreed, derived from a system wherein God or Dad (or, more often, both) was on top and you were on the bottom.

And it was no joke.

Whatever else one might think of authority, it was not funny. But after one had rewired ones self with LSD, authority — with its preening pomp, its affection for ridiculous rituals of office, its fulsome grandiloquence, and eventually, and sublimely, its tarantella around Mutually Assured Destruction — became hilarious to us and there wasnt much we could do about it.

No matter how huge and fearsome the puppets, once ones perceptions were wiped clean enough by the psychedelic solvent to behold their strings and the mechanical jerkiness of their behavior, it was hard to suppress the giggles. Though our hilarity has since been leavened with tragedy, loss, and a more appropriate sense of our own foolishness, were laughing still.

_Birth of A Psychedelic Culture _is a saga of holy heroism. The people in it were like the Lewis and Clark of the Mind. But it is also a cautionary tale and contained within it is a lot of the real reason that America had such a visceral immune reaction to our sudden, terrifying and transforming Otherness in the middle of its consciousness.

Before delightedly steering the train off its rails, we were given a glimpse of grace and infinity. But like all that is utterly true, the lightning was brief and the thunder rolls still.

In the beginning for me — and for many of us — there was the realization that religion was mostly the creation of God in man’s own image. Just as Tim Leary became furious at Catholicism shortly after hitting West Point, I bought a little Honda motorcycle and found that my dopily consoling Mormonism couldnt seem to ride along. Like the maddeningly glib Dick Alpert — and believe me, he was a man of many words in those days — I left monotheism for sex and velocity.

But there had been, even in a book as weird as the one the Angel Moroni purportedly gave Joseph Smith (Mark Twain called it chloroform in print), a spark of something. It was not religion, but you could almost see it from there.

I sped around with a longing for the Spirit that seemed inaccessible until sometime in 1964 when I read about the Good Friday Experiment in which, on Good Friday of 1962, Walter Pahnke, Tim Leary and the two battle-scarred saints of the Unnamable whose reminiscences you can read in the book (Ram Dass and Ralph Metzner), had given psilocybin to some divinity students in Boston Universitys Marsh chapel and — mirabile dictu! — they fucking saw God or something like It. And all because somebody gave them a pill.

Like most people raised by hick kids in the mountains, I was a mystic without ever having heard the word. If I could have a direct experience of The Thing Itself, without all that regulatory obligation wrapped around it, I would become whole again. After that, I read everything I could find about mystico-mimetic chemicals: Gordon Wassons 1957 article for Life magazine about magic mushrooms, Aldous Huxleys Doors of Perception, Bill Burroughss Yage Letters, etc. I wanted a piece of that communion wafer and so did a lot of other kids raised around the dreary wasteland of American piety.

In the fall of 1965, I entered Wesleyan University where both the man who was to become Ram Dass, as well as the man who sheltered and then spurned the Harvard Psilocybin Project, Dave McClelland, had taught shortly before. I knew about Leary, Alpert and Metzner and had my own copy of The Psychedelic Experience. But I thought they were still at Harvard. I was going to go find them.

Before I could get around to that pilgrimage, I found myself at a Vassar mixer one late night in late 1965 and met a strangely luminous Indian Brahmin fellow who stood apart. He asked me if I could give him a ride to the religious retreat where he was staying not far from Poughkeepsie and I agreed. So we wheeled around shiny narrow roads to Millbrook in a truly Biblical downpour and the next thing I knew I was looking at the headquarters of the Castalia Foundation.

He invited me in. I didnt know who lived there. Now, at that point, my heroes had not only been cast out of Harvard, but paradise as well. Inside the house it was not such a pretty sight. The social order had been whupped upside the head too many times already, but that didnt bother me. I had Forrest Gumped my way into the Temple of Delphi. Not long after that, I was fully enrolled in the Eastern Orthodox Church of LSD.

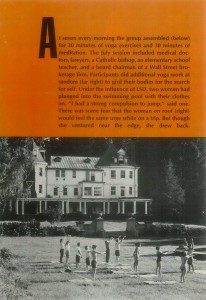

Millbrook (All image rights reserved)

A great deal more could be said about my initiation and the adventures that followed, but this is not about my long, strange trip. Besides, there are better stories about the perception of mysterium tremendum and its effect upon mere mortals. (Understanding the legend of Dr. Faustus might not be a bad start either).

I will say that there was a night in late 1966, I think, when I rode a motorcycle from Millbrook to Middletown during an ice storm and was, because of the acid, convinced that I could no more leave the road than an electron could escape the centerline of a linear accelerator.

I will also say that by then I’d switched my academic focus from physics to phenomenology with a particular focus on Medieval Christian mystics like St. Theresa, St. John of the Cross, and Meister Eckhart. I had a sign on my dorm room door displaying the following formula: [picture of me] + [skeletal schematic representation of the LSD-25 molecule] = [ picture of the Buddha ].The acid was working.

What I didn’t know then was that my best friend from prep school, a kid named Bob Weir, who had been strangely incommunicado since shortly after he worked on my family’s ranch, had been right next to another great fumarole of pharmaceutical whacketydoodah, the Acid Tests.

His little band, the Grateful Dead, had been part of an experiment in mass hallucination which seemed, from our East Coast view, to make Millbrook look like a Trappist monastery. It sounded to me like what these West Coast people were doing was a particularly blasphemous form of drug abuse, the spiritual equivalent of breaking into Chartres Cathedral and getting drunk on the communion wine.

But, while we were looking down our long patrician noses at these barbaric shenanigans, they were apparently producing transformations similar to our own. Five years later, Hunter S. Thompson recalled 1965 and 1966 in San Francisco like this (Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, pg 68):

There was madness in any direction, at any hour You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning. And that, I think, was the handle — that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail.

Yes. That seemed right. Even as we were dismantling the monotheistic model of God as Abusive Father, we were assembling another one — in our own image of course — more personally available through mysticism and generally more immanent than the Previous Dude, but still inclined to lend special sanction to the actions of a particular socio-political cohort which, happily, turned out to be ours. God, or Something Like It, was on our side this time.

The fact that God might turn up looking like a fat guy with an elephant head or as an aperture into pure, spirit-scalding Light, or even as Michael Hollingshead on a bad day, didnt matter to us. The Apocalypse was nigh. The Age of Aquarius had dawned, and God was no longer in his Heaven but getting down, right there inside of us and our holy pills.

By spring of 1967, Leary, Alpert, and Metzner had already started to feel the arrogance of this premise. All three had gone to India and two had come limping back. Personally, I was still accelerating into the radiant fog, and so was a large percentage of my swollen generational demographic.

The Gathering of the Tribes had taken place in Golden Gate Park in January of that year. Leary and Allen Ginsberg had turned up there along with the international press, and the coastal schism in the Church of Acid had been officially healed. Somewhere in there, Time magazine ran a cover story on The Hippies. A more attentive cultural observer than I would have known by that sign that wed reached our high-water mark.

Whatever my earlier misgivings about the Acid Tests, I had learned by then that my dear Weir had been part of this heresy. I was tickled to hear that the Grateful Dead were going to play their first New York gig at a Bleecker Street disco called the Cafe Au GoGo in June.

Barlow (all image rights reserved)

Early June 1967 was a mighty time, the reverberations of which are now as ubiquitous in American cultural history as is the Big Bang in the rest of the universe. As I remember it, the Dead played on June 6th. The Six Day war had broken out the day before. Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band had been released five days before, as had the Grateful Deads eponymous first record. I had helped make arrangements to take the Dead up to Millbrook the day after.

After the show, which was kind of forgettable, Weir and I wandered over to Washington Square Arch and were trying to debrief one another. It was steady work. It wasnt obvious that he had entirely passed the Acid Test. His eyes were all pupil, it seemed. He had the longest hair Id ever seen on a human with a penis. And he’d become a fellow of very few words.

While we were struggling with the acquisition of a common language, a pale green Ford Falcon station wagon leapt the curb fifteen feet away and, like evil clowns emerging in platoon strength from a tiny circus car, some ten Long Island toughs poured out of it and headed toward us. You could see with one eye that they weren’t from our side of a culture war that had already gotten ugly in America. Like T cells in jackboots, they took us for antigens and meant us harm.

As they were circling, Weir looked up and said mildly, ”You know, I sense violence in you guys, and whenever I feel it in myself, there’s a song I like to sing.” ( And Im thinking, ??! ) All of a sudden he’s chanting Hare Krishna, and what with my wondering ears should I hear but the toughs singing along. For about fifteen seconds. And then they beat the crap out of us.

So, as I drove my 550 horsepower Chevy Super Sport up the Taconic to Millbrook the next day, both Bobby and I looked like Wiley Coyote after a bad run-in with an Acme product. Also on board was a girl named Bos ( over whom I was totally goofy at the time), Phil Lesh, and Frank Zappa’s star chick singer, a hot number who called herself Uncle Meat.

We listened to war news from the Holy Land on the radio and we had on board a copy of Sgt. Pepper’s, which Id bought on the way out of town and which none of us had heard yet. I was trying to explain to my inamorata Bos, both of whose parents were Jewish psychiatrists, why I felt so moved by St. John of the Cross’s Dark Night of the Soul.

It was a moment in the ’60s, that day was.

When we got to the Hitchcock Mansion, it was pretty clear that whatever else the charming Dr. Leary was trying to tell the world, housekeeping tips were not being integrated into it. Few of the regulars remained. Ralph, Tim, and even Michael Hollingshead had reached a point the year before when they’d found Dr. Alperts manias so alarming that theyd sent him packing off to India. (Where he was, by this time, already in a dhoti and well on his way to becoming Baba Ram Dass. He dropped the Baba as soon as the wisdom actually kicked in.)

That night we all gathered in the second floor library and, with ecclesiastical ceremony, we put on Sgt. Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band. Nobody said a word while the record played. Many of us couldn’t have if we’d wanted to. I was so high I could taste the music and found the purple notes a little hard to chew. When the London Philharmonic’s last cacophonous notes trailed out of ’A Day in the Life,’ there was a portentous silence and Timmy intoned solemnly, “My work is complete.” Little did he know how right and how wrong he was.

I say this because while he and the rest of us crazy angels had truly delivered some form of apocalypse, it could not actually take effect in a couple of years or even a couple of generations. No revelation so culturally shattering was going to be universally accepted overnight. No generation that called itself now was going to find lengthy evolution palatable, but that was what was on our plate nonetheless.

Yes, the Beatles had dropped acid and the whole world had noticed, but not everyone was pleased. The Empire was about to strike back. Moreover, we had, with our giddy carnival frenzies and darker madnesses soon to come, sown the seeds of our own disaster. There was a moment in the fall of 1967 that I myself became convinced, with passionate intensity, that we were that rough beast Yeats had described. We were leading society into such a quagmire of narcissistic, self-reaffirming subjectivism that if we continued to Storm Heaven, as Jay Stevens put it, little of what might be a reasonable basis for polity or even what passes for civilization would survive our self-indulgence.

I went unhinged. I became psychotic and grandiose and decided to become what would have been America’s first suicide bomber. I was prepared to sound a warning with my own spattered flesh and that of innocent others. I would be the admonition on the front page of every paper that would slow the juggernaut of hideous Truth. I had the means and the moment. Fortunately, praise Providence, I was found out and stopped forty-five minutes short of my own vile apocalypse. I lived on Thorazine for a while after that.

But my intended mission attracted other willing soldiers. In my stead, we got Charlie Manson and Altamont. We got the behavioral sink of the long autumn that followed the Summer of Love. We got the Chicago Democratic Convention, the Weather Underground, the Symbionese Liberation Front, the communes that turned into rural slums overnight. What we got was the Bill.

Hunter S. Thompson put it very harshly but with some accuracy a few years later in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (pgs 178-179):

All those pathetically eager acid freaks who thought they could buy Peace and Understanding for three bucks a hit. But their loss and failure is ours, too. What Leary took down with him was the central illusion of a whole life-style that he helped to create a generation of permanent cripples, failed seekers, who never understood the essential old-mystic fallacy of the Acid Culture: the desperate assumption that somebody or at least some force — is tending the light at the end of the tunnel.

Who can blame the Rotarians of America for being alarmed? We became terrifying enough to scare ourselves. The Babbitry came down with a not ill-considered immune response that, however draconian its methods, was nevertheless their Apollonian duty just as appropriately as the creation of Dionysian chaos had seemed to be ours.

But perhaps even more unsettling to the Powers That Had Been was the fact that, as I mentioned earlier, in addition to calling into question their version of God-given authority, we now found them amusing.

Since there is nothing authority hates worse than being laughed at, the authorities resolved to make themselves even less funny. The harder the acid heads laughed, the more bellicose, pig-headed, and, well authoritarian the Powers became. And thus, instead of a quick abdication by the cultural forces that had been in charge of Western Civilization for two thousand years and a peaceful transfer of power to the laughing Aquarians, there commenced the forty year Mexican standoff that I call the War Between the Fifties and the Sixties.

Of course, this conflict had a lot of other names along the way, most of them delicious with the kind of dark irony it takes an acidhead to properly savor. There was the Viet Nam War, the War on Poverty, The War on Terror, both Wars on Iraq, and throughout, interwoven into every inch ofAmerican life, there was the War on ( Some ) Drugs. There was also, implicitly, the War on the Bill of Rights.

Whatever its other depraved social consequences — the millions jailed, the military dead and maimed, the deceit and denial at all levels of American society, particularly within the nuclear family — the War Between the Fifties and the Sixties endowed us with a golden age of irony. If you didn’t have a sense of irony, you were missing most of the fun, and, um, ironically, just about the only Americans who did have one were the acid heads. This created yet another badly hung loop as various iterations of We had to destroy the village in order to save it concatenated through the culture and, once again, we were the only ones laughing.

And then, lest we forget, throughout much of this period, and scarcely mentioned by anybody, acid head or Republican Whip, was the greatest surreality of all: the almost universal belief that somewhere and some time soon, someone would foul up and launch the nuclear storm that would glaze the planet with our elemental constituents. And if you couldn’t laugh at that, what could you laugh at?

Now, it seems many of these horrors may be consigned to the history of a future that never happened. While new horrors surely await us, very few still believe we’re likely to go toe-to-toe with the Russkies in nuclear combat as Slim Pickens put it in one of the most immortal lines of the 1960s.

Better still, the worst of the authoritarian prigs have so magnificently shot their wad during eight long years of Cheney/Bush that only those savagely beaten by their own fathers or the clergy support them now. Aside from the coming kerfuffle over war crimes indictments and ongoing skirmishes along the Mason-Dixon Line, the War Between the Fifties and the Sixties may be finally drawing to an end.

Indeed, as I write these words, the President of the United States, in addition to being black and self-admittedly smart and well-educated, strikes me as a fellow who probably dropped acid at some point. At the least, when asked if he inhaled, he replied, I thought that was the point.

Now that the worst of it may be over, perhaps it may become possible for various members of Congress, federal judges, ranked military officers, prominent clergy, and captains of industry — aside from the peculiarly honest Steve Jobs — to do as most of these, had they been brave enough, ought to have done decades ago and say in public:

There was a moment, years ago, when I took LSD. And, whatever the immediate consequences, it made me a different person than I would have been and different in ways I have been grateful for all this time.

That would be a mighty moment. Those who still live are all now older and wiser than we were in those literally heady days, and we may finally be ready to tell such truths without setting off another round of conflict. Ram Dass has come a long way along the path of the profound since I first met him as the maddeningly manipulative Dick Alpert.

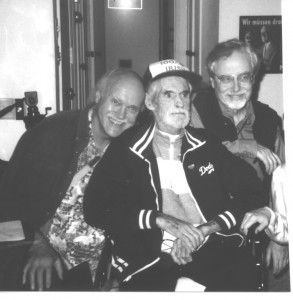

Ram Dass, Leary, Metzner (All image rights reserved)

Indeed, at one point some years ago, I was having dinner with him and confessed to a moral dilemma that I was having a hard time teasing apart. I cant even remember what it was now, but he cut through it snickety-snack, like a sword through the Gordian Knot, with a few well chosenwords.Thats the problem with you, man, I said, and continued with a concession I would not have made even to Baba Ram Dass, who turned up first at Wesleyan when he returned from India, still pretty full of self-promoting nonsense, Youre just a lot wiser than I am.

His eyes narrowed. ”Dont you lay that wisdom shit on me, Barlow,” he retorted, thereby defeating his own argument with its refutation. But even before then, he had uttered a motto that has been far more important to carrying the essential message of the sixties than ”Turn on. Tune in. Drop out” (which was actually coined by Marshall McLuhan and given toTim Leary since it didn’t fit McLuhan’s rap).

Ram Dass said, ”Be here now.”

And here we all are. Now. Ready at last with the patience, forgiveness, contrition and self-amusement necessary to continue the work in earnest. It is a good time to go back to the beginnings of the revolution still under way and take stock. It is a good time to read this book. Now.

(Through Sun Feb 9th, enter discount code “reality” at Synergetic Press’s site and receive 35% discount on this title, after purchase you will receive an e-mail with ANOTHER code for a FREE e-book of your choice, including ‘Mystic Chemist’)

John Perry Barlow is a writer, a former Wyoming rancher and Grateful Dead lyricist, and a founding member of the Electronic Frontier Foundation — an organization dedicated to the defense of freedom of speech_. _

Cover (All image rights reserved)

_ _

__ acid test Allen Ginsberg gathering of the tribes grateful dead Hunter S. Thompson LSD millbrook psilocybin Psychedelics ralph metzner Ram Dass Religion richard alpert Sixties Counterculture timothy leary

__ Facebook Comments

About the Author

][70]

[

author

@ // Not recently active

__ 1

Shares

__

- __ {{ share.shares }} [ {{ share.user.display_name }} ][70]

Related Posts

[70]: