15 KiB

| created_at | title | url | author | points | story_text | comment_text | num_comments | story_id | story_title | story_url | parent_id | created_at_i | _tags | objectID | year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-10-12T12:07:21.000Z | Why Every Country Has a Different Plug (2009) | http://gizmodo.com/5391271/giz-explains-why-every-country-has-a-different-fing-plug | JacobAldridge | 48 | 57 | 1444651641 |

|

10373969 | 2009 |

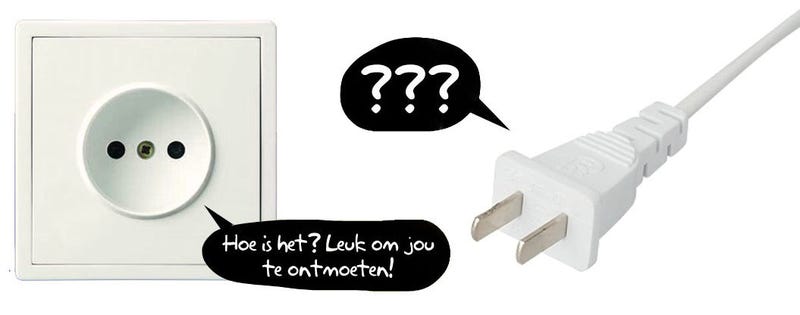

Ok, maybe not every country, but with at least 12 different sockets in widespread use it sure as hell feels like it to anyone who's ever traveled. So why in the world, literally, are there so many? Funny story!

The more you look at the writhing orgy of plugs in the world, the sillier it seems. If you buy a phone charger at the airport in Florida, you won't be able to use it when your flight lands in France. If you buy a three-pronged adapter for le portable in Paris, you might not be able to plug it in when your train drops you off in Germany. And when your flight finally bounces to a stop on the runway in London, get ready to buy a comically large adapter to tap into the grid there. But that's cool! You can take the same adapter to Singapore with you! And parts of Nigeria! Oh yeah, and if said charger doesn't support 240v power natively, make sure you buy a converter, or else it might explode.

Advertisement

And aside from a few oases, like the fledgling standardization of the Type C Europlug in the European Union, this is the picture all across the world.

I'd hesitate to refer to power sockets as a part of a country's culture, because they're plugs—they don't really mean anything. But in the sense that they're probably not going to change until they're forcefully replaced with something wildly new, it's kind of what they are.

What's Out There

Advertisement

Click for larger

There are around 12 major plug types in use today, each of which goes by whatever name their adoptive countries choose. For our purposes, we're going to stick with U.S. Department of Commerce International Trade Administration names (PDF), which are neat and alphabetical: America uses A and B plugs! Turkey uses type C! Etc. Thing is, these names are arbitrary: the letters are just assigned to make talking about these plugs less confusing—they don't actually mandate anything. They're not standards, in any meaningful sense of the word.

And even worse, these sockets are divided into two main groups: the 110-120v fellas, like the the ones we use in North America, and the 220-240v plugs, like most of the rest of the world uses. It's not that the plugs and sockets themselves are somehow tied to one voltage or another, but the devices and power grids they're attached to probably are.

Advertisement

How This Happened

The history of the voltage split is a pretty short story, and one you've probably heard bits and pieces of before. Edison's early experiments with direct current (DC) power in the late 1800s netted the first useful mainstream applications for electricity, but suffered from a tendency to lose voltage over long distances. Nonetheless, when Nikola Tesla invented a means of long-distance transmission with alternating current (AC) power, he was doing so in direct competition with Edison's technology, which happened to be 110v. He stuck with that. By the time people started to realize that 240v power might not be such a bad idea for the US, it was the 1950s, and switching was out of the question.

Words were exchanged, elephants were electrocuted, and eventually, the debate was settled: AC power was the only option, and national standardization started in earnest. Westinghouse Electric, the first company to buy Tesla's patents for power transmission, settled on an easy standard: 60Hz, and 110v. In Europe—Germany, specifically—a company called BEW exercised their monopoly to push things a little further. They settled somewhat arbitrarily on a 50Hz frequency, but more importantly jacked voltages up to 240, because, you know, MORE POWER. And so, the 240 standard slowly spread to the rest of the continent. All this happened before the turn of the century, by the way. It's an old beef.

Advertisement

For decades after the first standards, newfangled el-ec-trick-al dee-vices had to be patched directly into your house's wiring, which today sounds like a terrifying prospect. Then, too, it was: Harvey Hubbell's "Separable Attachment Plug"—which essentially allowed for non-bulb devices to be plugged into a light socket for power—was designed with a simple intention:

My invention has for its object to...do away with the possibility of arcing or sparking in making connection, so that electrical power in buildings may be utilized by persons having no electrical knowledge or skill.

Advertisement

Thanks, Harvey! He later adapted the original design to include a two-pronged flat-blade plug, which itself was refined into a three-pronged plug—the third prong is for grounding—by a guy named Philip Labre in 1928. This design saw a few changes over the years too, but it's pretty much the type Americans use now.

Here's the thing: Stories like that of Harvey Hubbell's plug were unfolding all over the world, each with their own twist on the concept. This was before electronics were globalized, and before country-to-country plug compatibility really mattered. The voltage debate had been pared down to two(ish) which made life a bit easier for power companies to set up shop across the world. [Note: There are technically more than two voltages in use, which reader Michael clarifies rather wonderfully here]. But once they were set up, who cared what style plug their customers used? What were you gonna do, lug your new vacuum cleaner across the ocean on a boat? Early efforts to standardize the plug by organizations like the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) had trouble taking hold—who were they to tell a country which plug to adopt?—and what little progress they did make was shattered by the Second World War.

Advertisement

Take the British plug. Today, it's a huge, three-pronged beast with a fuse built right into it—one of the weirder plugs in the world, to anyone who's had a chance to use one. But it isn't Britain's first plug, or even their first proprietary plug. In the early 1900s the Isles' cords were capped with the British Standard 546, or Type D hardware, which actually include six subversions of its own, all of which were physically incompatible with one another. This worked out fine until the Second World War, when they got the shit bombed out of them by Germany, and had to rebuild entire swaths of the country in the midst of a severe shortage of basic building supplies— copper, in particular. This made rewiring stuff an expensive proposition, so the government was all, "we need a new plug, stat!"

Here was the pitch: Instead of wiring each socket to a fuseboard somewhere in the house, which would take quite a bit of wire, why not just daisy-chain them together on one wire, and put the fuses in each plug? Hey presto, copper shortage, solved. This was called the British Standard 1363, and you can still find them dangling from wires today. Notice how even in the 1940s and '50s—practically yesterday!—the UK was devising a new type of plug without any regard for the rest of the world.

Advertisement

Now imagine every other developed country in the world doing the same thing, with a totally different set of historical circumstances. That's how we ended up here, blowing fuses in our Paris hotel rooms because our travel adapters' voltage warning were inexplicably written in Cyrillic. Oh, and it gets worse.

You know how the British had control over India for, like, ninety years? Well, along with exporting cricket and inflicting unquantifiable cultural damage, they showed the subcontinent how to plug stuff in, the British way! Problem is, they left in 1947. The BS 1363 plug—the new one—wasn't introduced until 1946, and didn't see widespread adoption until a few years later. So India still uses the old British plug, as does Sri Lanka, Nepal and Namibia. Basically, the best way to guess who's got which socket is to brush up on your WW1/WW2 history, and to have a deep passion for postcolonial literature. No, really.

Advertisement

Is There Any Hope for the Future?

No. I talked to Gabriela Ehrlich, head of communications for the International Electrotechnical Commission, which is still doing its thing over in Switzerland, and the outlook isn't great. "There are standards, and there is a plug that has been designed. The problem is, really, everyone's invested in their own system. It's difficult to get away from that."

When Holland's International Questions Commission first teamed up with the IEC to form a committee to talk about this exact problem in 1934. Meetings were stalled, there was some resistance, blah blah blah, and the committee was delayed until 1940. Then a war—a World War, even!—threw a stick in the committee's spokes, (or a fork in their socket? No?), and the issue was effectively dropped until about 1950, when the IEC realized that there were "limited prospects for any agreement even in this limited geographical region (Europe)." It'd be expensive to tear out everyone's sockets, and the need didn't feel that urgent, I guess.

Advertisement

Plus, the IEC can't force anyone to do anything—they're sort of like the UN General Assembly for electronics standards, which means they can issue them, but nobody has to follow them, no matter how good they are. As time passed, populations grew, and hundred of millions of sockets were installed all over the world. The prospect of switching hardware looked more and more ridiculous. Who would pay for it? Why would a country want to change? Wouldn't the interim, with mixed plug standards in the same country, be dangerous?

But the IEC didn't quite abandon hope, quietly pushing for a standard plug for decades after. And they even came up with some! In the late 80s, they came up with the IEC 60906 plug, a little, round-pronged number for 240v countries. Then they codified a flat-pronged plug for 110-120v countries, which happened to be perfectly compatible with the one we already use in the US. As of today, Brazil is the only country that plans to has adopt[ed] the IEC 60906, so, uh, there's that.

Advertisement

I asked Gabriela if there was any hope, any hope at all, for a future where plugs could just get along:

Maybe in the future you'll have induction charging; you have a device planted into your wall, and you have a [wireless] charging mechanism.

Advertisement

Last time I saw a wireless power prototype was at the Intel Developer Forum in 2008, and it looked like a science fair project: It consisted of two giant coils, just inches apart, which transmitted enough electricity to light a 40w light bulb. So yeah, we'll get this power plug problem all sorted by oh, let's say, 2050?

She took care to emphasize that the standards are still there for people to adopt, so countries could jump onboard, but even in a best-case scenario, for as long as we use wires we'll have at least two standards to deal with—a 110-120v flat plug and the 240-250v round plug. For now, the Commission is taking a more practical approach to dealing with the problem, issuing specs for things like laptop power bricks, which can handle both voltages and come with interchangeable lead wires, as well as as something near and dear to our hearts: "We have to move forward into plugs we can really control," Gabriela told me. She means new stuff like USB, which is turning into the de facto gadget charging standard. The most we can hope for is a future where AC outlets are invisible to us, sending power to newer, more universal plugs. My phone'll charge via USB just as well in Sub-Saharan Africa as it will in New York City; just give me the port.

Advertisement

In the meantime, this means that things really aren't going to change. Your Walmart shaver will still die if you plug it into a European socket with a bare adapter, Indians will still be reminded of the British Empire every time they unplug a laptop, Israel will have their own plug which works nowhere else in the world, and El Salvador, without a national standard, will continue to wrestle with 10 different kinds of plug.

In other words, sorry.

Many thanks to Gabriela Ehrlich and the IEC, as well as the Institute for Engineering and Technology and Wiring Matters (PDF), and USC Viterbi's illumin review. Map adapted from Wikimedia Commons by Intern Kyle

Advertisement

Still something you wanna know? Still can't figure out how to plug in your Bosnian knockoff iPhone? Send questions, tips, addenda or complaints to tips@gizmodo.com, with "Giz Explains" in the subject line.