36 KiB

| created_at | title | url | author | points | story_text | comment_text | num_comments | story_id | story_title | story_url | parent_id | created_at_i | _tags | objectID | year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017-12-12T23:00:26.000Z | Ernest Hemingway, the Art of Fiction No. 21 (1958) | https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4825/ernest-hemingway-the-art-of-fiction-no-21-ernest-hemingway | samclemens | 77 | 4 | 1513119626 |

|

15910297 | 1958 |

Paris Review - Ernest Hemingway, The Art of Fiction No. 21

-

* ###### Sign In-

* * * * * * [The Daily][1]

-

* [About][8]

* [Support][9]

* * * [

Subscribe

Our Winter issue _with …

_Hilton Als

Morgan Parker

Stacy Schiff

… and more.

Subscribe now →

* * * * ###### Sign In

* * * [The Daily][1]

* [The Review][2]

* [About][8]

* [Support][9]

* ###### [Subscribe][11]

Sign In

Remember me

Advertisement

Ernest Hemingway, The Art of Fiction No. 21

Interviewed by George Plimpton

Issue 18, Spring 1958

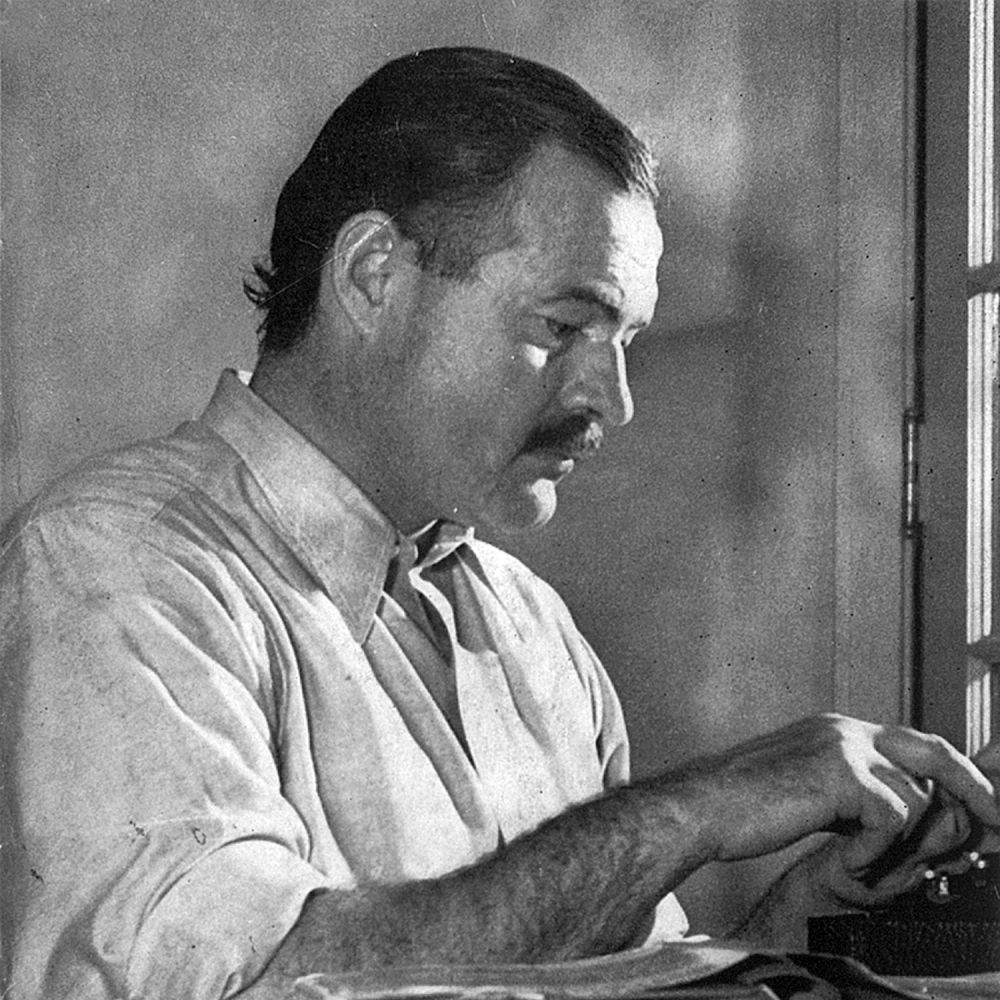

Ernest Hemingway, ca. 1939. Photograph by Lloyd Arnold

Ernest Hemingway, ca. 1939. Photograph by Lloyd Arnold

HEMINGWAY

You go to the races?

INTERVIEWER

Yes, occasionally.

HEMINGWAY

Then you read the Racing Form ... There you have the true art of fiction.

—Conversation in a Madrid café, May 1954

Ernest Hemingway writes in the bedroom of his house in the Havana suburb of San Francisco de Paula. He has a special workroom prepared for him in a square tower at the southwest corner of the house, but prefers to work in his bedroom, climbing to the tower room only when “characters” drive him up there.

The bedroom is on the ground floor and connects with the main room of the house. The door between the two is kept ajar by a heavy volume listing and describing The World’s Aircraft Engines. The bedroom is large, sunny, the windows facing east and south letting in the day’s light on white walls and a yellow-tinged tile floor.

The room is divided into two alcoves by a pair of chest-high bookcases that stand out into the room at right angles from opposite walls. A large and low double bed dominates one section, oversized slippers and loafers neatly arranged at the foot, the two bedside tables at the head piled seven-high with books. In the other alcove stands a massive flat-top desk with a chair at either side, its surface an ordered clutter of papers and mementos. Beyond it, at the far end of the room, is an armoire with a leopard skin draped across the top. The other walls are lined with white-painted bookcases from which books overflow to the floor, and are piled on top among old newspapers, bullfight journals, and stacks of letters bound together by rubber bands.

It is on the top of one of these cluttered bookcases—the one against the wall by the east window and three feet or so from his bed—that Hemingway has his “work desk”—a square foot of cramped area hemmed in by books on one side and on the other by a newspaper-covered heap of papers, manuscripts, and pamphlets. There is just enough space left on top of the bookcase for a typewriter, surmounted by a wooden reading board, five or six pencils, and a chunk of copper ore to weight down papers when the wind blows in from the east window.

A working habit he has had from the beginning, Hemingway stands when he writes. He stands in a pair of his oversized loafers on the worn skin of a lesser kudu—the typewriter and the reading board chest-high opposite him.

When Hemingway starts on a project he always begins with a pencil, using the reading board to write on onionskin typewriter paper. He keeps a sheaf of the blank paper on a clipboard to the left of the typewriter, extracting the paper a sheet at a time from under a metal clip that reads “These Must Be Paid.” He places the paper slantwise on the reading board, leans against the board with his left arm, steadying the paper with his hand, and fills the paper with handwriting which through the years has become larger, more boyish, with a paucity of punctuation, very few capitals, and often the period marked with an X. The page completed, he clips it facedown on another clipboard that he places off to the right of the typewriter.

Hemingway shifts to the typewriter, lifting off the reading board, only when the writing is going fast and well, or when the writing is, for him at least, simple: dialogue, for instance.

He keeps track of his daily progress—“so as not to kid myself”—on a large chart made out of the side of a cardboard packing case and set up against the wall under the nose of a mounted gazelle head. The numbers on the chart showing the daily output of words differ from 450, 575, 462, 1250, back to 512, the higher figures on days Hemingway puts in extra work so he won’t feel guilty spending the following day fishing on the Gulf Stream.

A man of habit, Hemingway does not use the perfectly suitable desk in the other alcove. Though it allows more space for writing, it too has its miscellany: stacks of letters; a stuffed toy lion of the type sold in Broadway nighteries; a small burlap bag full of carnivore teeth; shotgun shells; a shoehorn; wood carvings of lion, rhino, two zebras, and a wart-hog—these last set in a neat row across the surface of the desk—and, of course, books: piled on the desk, beside tables, jamming the shelves in indiscriminate order—novels, histories, collections of poetry, drama, essays. A look at their titles shows their variety. On the shelf opposite Hemingway’s knee as he stands up to his “work desk” are Virginia Woolf’s The Common Reader, Ben Ames Williams’s House Divided, The Partisan Reader, Charles A. Beard’s The Republic, Tarle’s Napoleon’s Invasion of Russia, How Young You Look by Peggy Wood, Alden Brooks’s Shakespeare and the Dyer’s Hand, Baldwin’s African Hunting, T. S. Eliot’s Collected Poems, and two books on General Custer’s fall at the battle of the Little Big Horn.

The room, however, for all the disorder sensed at first sight, indicates on inspection an owner who is basically neat but cannot bear to throw anything away—especially if sentimental value is attached. One bookcase top has an odd assortment of mementos: a giraffe made of wood beads; a little cast-iron turtle; tiny models of a locomotive; two jeeps and a Venetian gondola; a toy bear with a key in its back; a monkey carrying a pair of cymbals; a miniature guitar; and a little tin model of a U.S. Navy biplane (one wheel missing) resting awry on a circular straw place mat—the quality of the collection that of the odds-and-ends which turn up in a shoebox at the back of a small boy’s closet. It is evident, though, that these tokens have their value, just as three buffalo horns Hemingway keeps in his bedroom have a value dependent not on size but because during the acquiring of them things went badly in the bush, yet ultimately turned out well. “It cheers me up to look at them,” he says.

Hemingway may admit superstitions of this sort, but he prefers not to talk about them, feeling that whatever value they may have can be talked away. He has much the same attitude about writing. Many times during the making of this interview he stressed that the craft of writing should not be tampered with by an excess of scrutiny—“that though there is one part of writing that is solid and you do it no harm by talking about it, the other is fragile, and if you talk about it, the structure cracks and you have nothing.”

As a result, though a wonderful raconteur, a man of rich humor, and possessed of an amazing fund of knowledge on subjects which interest him, Hemingway finds it difficult to talk about writing—not because he has few ideas on the subject, but rather because he feels so strongly that such ideas should remain unexpressed, that to be asked questions on them “spooks” him (to use one of his favorite expressions) to the point where he is almost inarticulate. Many of the replies in this interview he preferred to work out on his reading board. The occasional waspish tone of the answers is also part of this strong feeling that writing is a private, lonely occupation with no need for witnesses until the final work is done.

This dedication to his art may suggest a personality at odds with the rambunctious, carefree, world-wheeling Hemingway-at-play of popular conception. The fact is that Hemingway, while obviously enjoying life, brings an equivalent dedication to everything he does—an outlook that is essentially serious, with a horror of the inaccurate, the fraudulent, the deceptive, the half-baked.

Nowhere is the dedication he gives his art more evident than in the yellow-tiled bedroom—where early in the morning Hemingway gets up to stand in absolute concentration in front of his reading board, moving only to shift weight from one foot to another, perspiring heavily when the work is going well, excited as a boy, fretful, miserable when the artistic touch momentarily vanishes—slave of a self-imposed discipline which lasts until about noon when he takes a knotted walking stick and leaves the house for the swimming pool where he takes his daily half-mile swim.

INTERVIEWER

Are these hours during the actual process of writing pleasurable?

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

Very.

INTERVIEWER

Could you say something of this process? When do you work? Do you keep to a strict schedule?

HEMINGWAY

When I am working on a book or a story I write every morning as soon after first light as possible. There is no one to disturb you and it is cool or cold and you come to your work and warm as you write. You read what you have written and, as you always stop when you know what is going to happen next, you go on from there. You write until you come to a place where you still have your juice and know what will happen next and you stop and try to live through until the next day when you hit it again. You have started at six in the morning, say, and may go on until noon or be through before that. When you stop you are as empty, and at the same time never empty but filling, as when you have made love to someone you love. Nothing can hurt you, nothing can happen, nothing means anything until the next day when you do it again. It is the wait until the next day that is hard to get through.

INTERVIEWER

Can you dismiss from your mind whatever project you’re on when you’re away from the typewriter?

HEMINGWAY

Of course. But it takes discipline to do it and this discipline is acquired. It has to be.

INTERVIEWER

Do you do any rewriting as you read up to the place you left off the day before? Or does that come later, when the whole is finished?

HEMINGWAY

I always rewrite each day up to the point where I stopped. When it is all finished, naturally you go over it. You get another chance to correct and rewrite when someone else types it, and you see it clean in type. The last chance is in the proofs. You’re grateful for these different chances.

INTERVIEWER

How much rewriting do you do?

HEMINGWAY

It depends. I rewrote the ending to Farewell to Arms, the last page of it, thirty-nine times before I was satisfied.

INTERVIEWER

Was there some technical problem there? What was it that had stumped you?

HEMINGWAY

Getting the words right.

Want to keep reading?

Subscribe and save nearly 40%.

[

Subscribe Now

Already a subscriber? Sign in below.

Remember me

-

][16] [

-

][16] [

-

- Last / Next

Article

- Last / Next

-

- View

Manuscript

- View

-

- Last / Next Article

Share

More from Issue 18, Spring 1958

[ ![][17] ][18]

[Buy this issue!][18]

-

Fiction

- [ Jack Cope

[Kalahari Rose][19]

* [ Philip Roth

[The Conversion of the Jews][20]

* [ Gordon Woodward

[The Night Drivers][21]

-

Interview

- [ Ernest Hemingway

[The Art of Fiction No. 21][22]

-

Poetry

- [ Robert Bly

[The Fire of Despair Has Been Our Saviour][23]

* [ George P. Elliott

[Chinese Boxes][24]

* [ Robert Huff

[The Lay Brother][25]

* [ D.J. Hughes

[Lord Chandos to His Wife][26]

* [ Joseph Langland

[Hounds][27]

* [ W. S. Merwin

[Aunt Alma][28]

* [ W. S. Merwin

[Nothing New][29]

* [ Louis Simpson

[Illusions of the Moonlight][30]

* [ Louis Simpson

[Old Soldier][31]

* [ W. D. Snodgrass

The Campus on the Hill

][32] * [ William Stafford

Requiem

][33] * [ George Starbuck

And Then, It May Be Saturday

][34] * [ Frederick Tibbetts

Gli Scafari

][35] * [ Frederick Tibbetts

Fire in a Dark Landscape

][36] * [ Frederick Tibbetts

Distinctions

][37] * [ James Wright

To L., Asleep

][38]

-

Feature

- [ Alberto Giacometti

Giacometti at the Salon d' Auto

][39]

-

Art

- [ Vali

Seven Drawings

][40] * [ Alberto Giacometti

Eight Drawings

][41]

You Might Also Like

[

![][42]

Twelve Illustrated Dust Jackets

By The Paris Review February 22, 2018 ][43] [

![][44]

Yvan Alagbé's "Dyaa"

By Yvan Alagbé February 21, 2018 ][45] [

![][46]

The Night in My Hair: Henna, Syria, and the Muslim Ban

By Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar February 21, 2018 ][47] [

![][48]

The Real Scandal in Academia

By EJ Levy February 20, 2018 ][49]

From the Archive

[

![][50]

Dads Behaving Badly

By Dan Piepenbring June 16, 2017 ][51] [

![][52]

Chubby Boys and Chubby Girls

By Steve Gianakos November 24, 2015 ][53]

Staff Picks

[

![][54]

Staff Picks: Tattoos, Death Grips, and Love Letters

By The Paris Review February 16, 2018 ][55] [

![][56]

Staff Picks: Rachel Lyon, Radiohead, and Richard Pryor

By The Paris Review February 9, 2018 ][57]

Advertisement

[

Current Issue No. 223

Our Winter issue _with …

_Hilton Als

Morgan Parker

Stacy Schiff

… and more.

Get this issue now!

]11

![Revel][58]

Featured Audio

Ernest Hemingway

The Art of Fiction No. 21

Cipriani, October 2003

The fact that I am interrupting serious work to answer these questions proves that I am so stupid that I should be penalized severely. I will be. Don't worry

00:00 /

![The Daily Rower][59]

Suggested Reading

[

![Twelve Illustrated Dust Jackets][60]

Twelve Illustrated Dust Jackets

By The Paris Review February 22, 2018

We've all been told told not to judge a book by its cover, but what about judging a decade, an artistic moment, or a society? In his latest collection, The Illustrated Dust Jacket: 1920–1970, illustration professor Martin Salisbury traces th…

![The Daily Rower][59]

The Daily

Arts & Culture

][61] [

Hunter S. Thompson, The Art of Journalism No. 1

By Hunter S. Thompson

![undefined][62]

In an October 1957 letter to a friend who had recommended he read Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead, Hunter S. Thompson wrote, “Although I don’t feel that it’s at all necessary to tell you how I feel about the principle of individuality, I know that I’m going to have to spend the rest of my life expressing it one way or another, and I think that I’ll accomplish more by expressing it on the keys of a typewriter than by letting it express itself in sudden outbursts of frustrated violence. . . .”

Thompson carved out his niche early. He was born in 1937, in Louisville, Kentucky, where his fiction and poetry earned him induction into the local Athenaeum Literary Association while he was still in high school. Thompson continued his literary pursuits in the United States Air Force, writing a weekly sports column for the base newspaper. After two years of service, Thompson endured a series of newspaper jobs—all of which ended badly—before he took to freelancing from Puerto Rico and South America for a variety of publications. The vocation quickly developed into a compulsion.

Thompson completed The Rum Diary, his only novel to date, before he turned twenty-five; bought by Ballantine Books, it finally was published—to glowing reviews—in 1998. In 1967, Thompson published his first nonfiction book, Hell’s Angels, a harsh and incisive firsthand investigation into the infamous motorcycle gang then making the heartland of America nervous.

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which first appeared in Rolling Stone in November 1971, sealed Thompson’s reputation as an outlandish stylist successfully straddling the line between journalism and fiction writing. As the subtitle warns, the book tells of “a savage journey to the heart of the American Dream” in full-tilt gonzo style—Thompson’s hilarious first-person approach—and is accented by British illustrator Ralph Steadman’s appropriate drawings.

His next book, Fear and Loathing: On the Campaign Trail ’72, was a brutally perceptive take on the 1972 Nixon-McGovern presidential campaign. A self-confessed political junkie, Thompson chronicled the 1992 presidential campaign in _Better than Sex _(1994). Thompson’s other books include _The Curse of Lono _(1983), a bizarre South Seas tale, and three collections of Gonzo Papers: _The Great Shark Hunt _(1979), Generation of Swine (1988) and Songs of the Doomed (1990).

In 1997, The Proud Highway: Saga of a Desperate Southern Gentleman, 1955-1967, the first volume of Thompson’s correspondence with everyone from his mother to Lyndon Johnson, was published. The second volume of letters, Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist, 1968-1976, has just been released.

•

Located in the mostly posh neighborhood of western Colorado’s Woody Creek Canyon, ten miles or so down-valley from Aspen, Owl Farm is a rustic ranch with an old-fashioned Wild West charm. Although Thompson’s beloved peacocks roam his property freely, it’s the flowers blooming around the ranch house that provide an unexpected high-country tranquility. Jimmy Carter, George McGovern and Keith Richards, among dozens of others, have shot clay pigeons and stationary targets on the property, which is a designated Rod and Gun Club and shares a border with the White River National Forest. Almost daily, Thompson leaves Owl Farm in either his Great Red Shark Convertible or Jeep Grand Cherokee to mingle at the nearby Woody Creek Tavern.

Visitors to Thompson’s house are greeted by a variety of sculptures, weapons, boxes of books and a bicycle before entering the nerve center of Owl Farm, Thompson’s obvious command post on the kitchen side of a peninsula counter that separates him from a lounge area dominated by an always-on Panasonic TV, always tuned to news or sports. An antique upright piano is piled high and deep enough with books to engulf any reader for a decade. Above the piano hangs a large Ralph Steadman portrait of “Belinda”—the Slut Goddess of Polo. On another wall covered with political buttons hangs a Che Guevara banner acquired on Thompson’s last tour of Cuba. On the counter sits an IBM Selectric typewriter—a Macintosh computer is set up in an office in the back wing of the house.

The most striking thing about Thompson’s house is that it isn’t the weirdness one notices first: it’s the words. They’re everywhere—handwritten in his elegant lettering, mostly in fading red Sharpie on the blizzard of bits of paper festooning every wall and surface: stuck to the sleek black leather refrigerator, taped to the giant TV, tacked up on the lampshades; inscribed by others on framed photos with lines like, “For Hunter, who saw not only fear and loathing, but hope and joy in ’72—George McGovern”; typed in IBM Selectric on reams of originals and copies in fat manila folders that slide in piles off every counter and table top; and noted in many hands and inks across the endless flurry of pages.

Thompson extricates his large frame from his ergonomically correct office chair facing the TV and lumbers over graciously to administer a hearty handshake or kiss to each caller according to gender, all with an easy effortlessness and unexpectedly old-world way that somehow underscores just who is in charge.

•

We talked with Thompson for twelve hours straight. This was nothing out of the ordinary for the host: Owl Farm operates like an eighteenth-century salon, where people from all walks of life congregate in the wee hours for free exchanges about everything from theoretical physics to local water rights, depending on who’s there. Walter Isaacson, managing editor of Time, was present during parts of this interview, as were a steady stream of friends. Given the very late hours Thompson keeps, it is fitting that the most prominently posted quote in the room, in Thompson’s hand, twists the last line of Dylan Thomas’s poem “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night”: “Rage, rage against the coming of the light.”

For most of the half-day that we talked, Thompson sat at his command post, chain-smoking red Dunhills through a German-made gold-tipped cigarette filter and rocking back and forth in his swivel chair. Behind Thompson’s sui generis personality lurks a trenchant humorist with a sharp moral sensibility. His exaggerated style may defy easy categorization, but his career-long autopsy on the death of the American dream places him among the twentieth century’s most exciting writers. The comic savagery of his best work will continue to electrify readers for generations to come.

•

. . . I have stolen more quotes and thoughts and purely elegant little starbursts of writing from the Book of Revelation than from anything else in the English Language—and it is not because I am a biblical scholar, or because of any religious faith, but because I love the wild power of the language and the purity of the madness that governs it and makes it music.

HUNTER S. THOMPSON

Well, wanting to and having to are two different things. Originally I hadn’t thought about writing as a solution to my problems. But I had a good grounding in literature in high school. We’d cut school and go down to a café on Bardstown Road where we would drink beer and read and discuss Plato’s parable of the cave. We had a literary society in town, the Athenaeum; we met in coat and tie on Saturday nights. I hadn’t adjusted too well to society—I was in jail for the night of my high school graduation—but I learned at the age of fifteen that to get by you had to find the one thing you can do better than anybody else . . . at least this was so in my case. I figured that out early. It was writing. It was the rock in my sock. Easier than algebra. It was always work, but it was always worthwhile work. I was fascinated early by seeing my byline in print. It was a rush. Still is.

When I got to the Air Force, writing got me out of trouble. I was assigned to pilot training at Eglin Air Force Base near Pensacola in northwest Florida, but I was shifted to electronics . . . advanced, very intense, eight-month school with bright guys . . . I enjoyed it but I wanted to get back to pilot training. Besides, I’m afraid of electricity. So I went up there to the base education office one day and signed up for some classes at Florida State. I got along well with a guy named Ed and I asked him about literary possibilities. He asked me if I knew anything about sports, and I said that I had been the editor of my high-school paper. He said, “Well, we might be in luck.” It turned out that the sports editor of the base newspaper, a staff sergeant, had been arrested in Pensacola and put in jail for public drunkenness, pissing against the side of a building; it was the third time and they wouldn’t let him out.

So I went to the base library and found three books on journalism. I stayed there reading them until it closed. Basic journalism. I learned about headlines, leads: who, when, what, where, that sort of thing. I barely slept that night. This was my ticket to ride, my ticket to get out of that damn place. So I started as an editor. Boy, what a joy. I wrote long Grantland Rice-type stories. The sports editor of my hometown Louisville Courier Journal always had a column, left-hand side of the page. So I started a column.

By the second week I had the whole thing down. I could work at night. I wore civilian clothes, worked off base, had no hours, but I worked constantly. I wrote not only for the base paper, The Command Courier, but also the local paper, The Playground News. I’d put things in the local paper that I couldn’t put in the base paper. Really inflammatory shit. I wrote for a professional wrestling newsletter. The Air Force got very angry about it. I was constantly doing things that violated regulations. I wrote a critical column about how Arthur Godfrey, who’d been invited to the base to be the master of ceremonies at a firepower demonstration, had been busted for shooting animals from the air in Alaska. The base commander told me: “Goddamn it, son, why did you have to write about Arthur Godfrey that way?”

When I left the Air Force I knew I could get by as a journalist. So I went to apply for a job at Sports Illustrated. I had my clippings, my bylines, and I thought that was magic . . . my passport. The personnel director just laughed at me. I said, “Wait a minute. I’ve been sports editor for two papers.” He told me that their writers were judged not by the work they’d done, but where they’d done it. He said, “Our writers are all Pulitzer Prize winners from The New York Times. This is a helluva place for you to start. Go out into the boondocks and improve yourself.”

I was shocked. After all, I’d broken the Bart Starr story.

INTERVIEWER

What was that?

THOMPSON

At Eglin Air Force Base we always had these great football teams. The Eagles. Championship teams. We could beat up on the University of Virginia. Our bird-colonel Sparks wasn’t just any yo-yo coach. We recruited. We had these great players serving their military time in ROTC. We had Zeke Bratkowski, the Green Bay quarterback. We had Max McGee of the Packers. Violent, wild, wonderful drunk. At the start of the season McGee went AWOL, appeared at the Green Bay camp and he never came back. I was somehow blamed for his leaving. The sun fell out of the firmament. Then the word came that we were getting Bart Starr, the All-American from Alabama. The Eagles were going to roll! But then the staff sergeant across the street came in and said, “I’ve got a terrible story for you. Bart Starr’s not coming.” I managed to break into an office and get out his files. I printed the order that showed he was being discharged medically. Very serious leak.

INTERVIEWER

The Bart Starr story was not enough to impress Sports Illustrated?

THOMPSON

The personnel guy there said, “Well, we do have this trainee program.” So I became a kind of copy boy.

INTERVIEWER

You eventually ended up in San Francisco. With the publication in 1967 of Hell’s Angels, your life must have taken an upward spin.

THOMPSON

All of a sudden I had a book out. At the time I was twenty-nine years old and I couldn’t even get a job driving a cab in San Francisco, much less writing. Sure, I had written important articles for The Nation and The Observer, but only a few good journalists really knew my byline. The book enabled me to buy a brand new BSA 650 Lightning, the fastest motorcycle ever tested by Hot Rod magazine. It validated everything I had been working toward. If Hell’s Angels hadn’t happened I never would have been able to write Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas or anything else. To be able to earn a living as a freelance writer in this country is damned hard; there are very few people who can do that. Hell’s Angels all of a sudden proved to me that, Holy Jesus, maybe I can do this. I knew I was a good journalist. I knew I was a good writer, but I felt like I got through a door just as it was closing.

INTERVIEWER

With the swell of creative energy flowing throughout the San Francisco scene at the time, did you interact with or were you influenced by any other writers?

THOMPSON

Ken Kesey for one. His novels One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Sometimes a Great Notion had quite an impact on me. I looked up to him hugely. One day I went down to the television station to do a roundtable show with other writers, like Kay Boyle, and Kesey was there. Afterwards we went across the street to a local tavern and had several beers together. I told him about the Angels, who I planned to meet later that day, and I said, “Well, why don’t you come along?” He said, “Whoa, I’d like to meet these guys.” Then I got second thoughts, because it’s never a good idea to take strangers along to meet the Angels. But I figured that this was Ken Kesey, so I’d try. By the end of the night Kesey had invited them all down to La Honda, his woodsy retreat outside of San Francisco. It was a time of extreme turbulence—riots in Berkeley. He was always under assault by the police—day in and day out, so La Honda was like a war zone. But he had a lot of the literary, intellectual crowd down there, Stanford people also, visiting editors, and Hell’s Angels. Kesey’s place was a real cultural vortex.

![Fiction][63]

From the Archive, Issue 156

Interview

][64]

Ernest Hemingway

The Art of Fiction No. 21

Cipriani, October 2003

The fact that I am interrupting serious work to answer these questions proves that I am so stupid that I should be penalized severely. I will be. Don't worry

00:00 /

![The Daily Rower][59]

Newsletter

Sign up for the Paris Review newsletter and keep up with news, parties, readings, and more.

Sign Up

[

Events

Join the writers and staff of The Paris Review at our next event.

][65]

[

Store

Visit our store to buy archival issues of the magazine, prints, T-shirts, and accessories.

][66]

![du Bois][67]

- Subscribe

- [Store][66]

- [Contact Us][68]

- [Jobs][69]

- [Submissions][70]

- [Masthead][71]

- [Prizes][72]

- [Bookstores][73]

- [Events][65]

- [Media Kit][74]

- [Audio][75]

- [Video][76]

- [Privacy][77]

- [Terms & Conditions][78]

- Subscribe

- [Store][66]

- [Contact Us][68]

- [Masthead][71]

- [Prizes][72]

- [Bookstores][73]

- [Events][65]

- [Media Kit][74]

- [Privacy][77]

- [Jobs][69]

- [Video][76]

- [Audio][75]

- [Submissions][70]

- [Terms & Conditions][78]

This site was created in collaboration with [Strick&Williams][79], [Tierra Innovation][80], and the staff of The Paris Review.

©2018 The Paris Review

[16]: [17]: https://www.theparisreview.org/il/a519d10b4e/medium/Issue018_3D.png [18]: http://store.theparisreview.org/cart/54327342:1 [19]: https://www.theparisreview.org/fiction/4829/kalahari-rose-jack-cope [20]: https://www.theparisreview.org/fiction/4830/the-conversion-of-the-jews-philip-roth [21]: https://www.theparisreview.org/fiction/4831/the-night-drivers-gordon-woodward [22]: https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4825/the-art-of-fiction-no-21-ernest-hemingway [23]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4832/the-fire-of-despair-has-been-our-saviour-robert-bly [24]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4833/chinese-boxes-george-p-elliott [25]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4834/the-lay-brother-robert-huff [26]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4835/lord-chandos-to-his-wife-dj-hughes [27]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4836/hounds-joseph-langland [28]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4837/aunt-alma-w-s-merwin [29]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/6601/nothing-new-w-s-merwin [30]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/6600/illusions-of-the-moonlight-louis-simpson [31]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4838/old-soldier-louis-simpson [32]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4839/the-campus-on-the-hill-w-d-snodgrass [33]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4840/requiem-william-stafford [34]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4841/and-then-it-may-be-saturday-george-starbuck [35]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/6598/gli-scafari-frederick-tibbetts [36]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/6599/fire-in-a-dark-landscape-frederick-tibbetts [37]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4842/distinctions-frederick-tibbetts [38]: https://www.theparisreview.org/poetry/4843/to-l-asleep-james-wright [39]: https://www.theparisreview.org/letters-essays/4826/giacometti-at-the-salon-d-auto-alberto-giacometti [40]: https://www.theparisreview.org/art-photography/4846/seven-drawings-vali- [41]: https://www.theparisreview.org/art-photography/4844/eight-drawings-alberto-giacometti [42]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/p34-35_idj-e1518797709506.jpg [43]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/?post_type=post&p=121666 [44]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/yvan.jpg [45]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/?post_type=post&p=121527 [46]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/hairhenna.jpg [47]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/?post_type=post&p=121767 [48]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/collectionofpulpsmallforme.jpg [49]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/?post_type=post&p=121740 [50]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/albundy.jpg [51]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/?post_type=post&p=111865 [52]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/screen-shot-2015-11-24-at-6.32.33-pm.png [53]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/?post_type=post&p=92283 [54]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/pic-e1518799664925.jpeg [55]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/?post_type=post&p=121664 [56]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/karen.jpg [57]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/?post_type=post&p=121404 [58]: https://www.theparisreview.org/dist/theme/issue_223/hadada-hover.jpg [59]: https://www.theparisreview.org/dist/theme/issue_223/rower.png [60]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/p106a_idj.jpg [61]: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2018/02/22/twelve-illustrated-dust-jackets/ [62]: https://www.theparisreview.org/il/fdb8a09feb/large/Hunter-S-Thompson.jpg "undefined" [63]: https://www.theparisreview.org/dist/theme/issue_223/lightpost.png [64]: https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/619/the-art-of-journalism-no-1-hunter-s-thompson [65]: https://www.theparisreview.org/events [66]: http://store.theparisreview.org/ [67]: https://www.theparisreview.org/images/placeholder-cover.gif [68]: https://www.theparisreview.org/contact [69]: https://www.theparisreview.org/about/jobs [70]: https://www.theparisreview.org/about/submissions [71]: https://www.theparisreview.org/about/masthead [72]: https://www.theparisreview.org/about/prizes [73]: https://www.theparisreview.org/about/bookstores [74]: https://www.theparisreview.org/about/media-kit [75]: https://www.theparisreview.org/audio [76]: https://www.theparisreview.org/video [77]: https://www.theparisreview.org/privacy-policy [78]: https://www.theparisreview.org/terms-and-conditions [79]: http://strickandwilliams.com/ [80]: http://www.tierra-innovation.com/